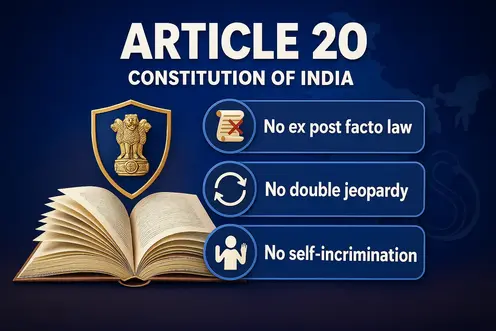

Introduction: ARTICLE 20 of the Indian Constitution

“It is better that ten guilty persons escape than that one innocent suffer.” — William Blackstone

No legal principle better captures the spirit of justice in this way. The idea that fairness must be uppermost to retribution captures the spirit of Article 20 of the Constitution of India.

Found in Part III — Fundamental Rights, Article 20 prohibits conviction for some offences. In so doing, the Article protects everyone from exceptional punishment, while also requiring that justice, when it occurs, is not vengeance, but humane, reasoned, and rule-based.

Article 20 serves as an ethical guide to criminal law, ensuring that state power always respects individual dignity. Article 20 provides for this protection through the following three bases –

- No ex post facto law,

- No double jeopardy, and

- No self-incrimination.

Conversely, Article 20 protects fairness in criminal trials, that punishment can only follow guilt established through process, and never before.

Read about why Padma awards are not banned even after having article 18.

Historical & Philosophical Roots of Criminal Justice

Justice, in all societies, developed as a counterbalance to power, and continued to evolve. From the earliest scrolls through to modern day constitutions, societies have attempted to develop limits to power to achieve fairness.

Article 20 of the Indian Constitution encompasses contemporary democratic ideals as well as ancient ethical tenets which saw justice as a sine qua non for government.

a. Ancient Indian Thought: Nyaya and Dandaneeti

In antiquity, Nyaya (justice) and Dandaneeti (just punishment) were the two cornerstones of social order in India. Texts such as Manusmriti and Arthashastra viewed justice as a right that the ruler owed to the people, not as a gift the ruler could give or withhold according to Dharma, the moral order of the universe.

Kautilya’s Arthashastra articulated a principle which is remarkably modern in its implications: punishment should be proportionate to both the intent of the offender and the nature of the offence. He differentiated between actions committed with intent and those which were unintentional, and counselled that a king should be the protector, not the prosecutor, of his people.

“The principal end of punishment is not the attainment of revenge, but the maintenance of order and welfare of the state.” — Arthashastra, Bk. 3

This ancient emphasis on fairness and proportionality constitutes the philosophical foundation of Article 20’s prohibition on arbitrary or retroactive punishment.

b. Medieval Thinkers: Law and Conscience

During periods of the Medieval period, Islamic law recognized and practice in the Delhi Sultanate and Mughal Empire would recognize Qanoon-e-Adl, or the “Law of Justice,” an important development in the modern era.

Combined together, these scholars laid the philosophical foundation for Article 20 — converting justice from an act of whim of the ruler’s mercy to that of a right of the citizen.

This principle required that individuals give confessions completely voluntarily and institutionalized the prohibition of coercing confessions through threats or torture. This may perhaps be the most early version of the right against self-incrimination as we understand it today.

Similarly, Emperor Akbar’s policy of Sulh-i-kul (universality of peace) went further to even espouse compassion in governance and moral abstinence from punitive measures. He believed that justice should unite society and not divide.

Medieval Indian thinkers incorporated law with ethics and power with accountability in their concept of justice, mirroring the moral abstinence that Article 20 reiterates centuries later.

c. European Enlightenment & Legal Philosophy

The modern version of Article 20 derives from European Enlightenment thought, wherein thinkers scrutinized state absolutism and arbitrary punishment.

Cesare Beccaria, in his landmark work On Crimes and Punishments (1764), condemned retrospective criminal laws by saying:

“. . .only laws made prior to the act can make determination of guilt.”

This directly inspired the principle of no ex post facto laws.

John Locke and Montesquieu propounded definitions around individual liberty and separation of powers, opining that the State cannot be both the jury and executioner.

Jeremy Bentham and William Blackstone subsequently developed a theory of legal certainty – being punishment must be predictable and proportionate, and trials must uphold rational justice and not simply seek revenge.

Constitutional Text and Essence of Article 20

Article 20 of the Indian Constitution serves as a guardian of fairness in criminal law. It protects against the possible misuse of legislative and executive power in criminal process. Article 20 provides:

“Protection in respect of conviction for offences.”

Article 20 of the Indian constitution has three clauses, each protecting a unique interest of justice:

Clause Provision Core Principle

20(1) No ex post facto law

The law cannot punish anyone retroactively; criminal laws apply only from the date they come into force.

20(2) No double jeopardy

The state cannot prosecute or punish anyone twice for the same facts.

20(3) No self-incrimination

The authorities cannot compel anyone to act as a witness against themselves.

Each of these clauses actively protects citizens: the law prevents punishing anyone without a valid law, stops the state from trying anyone twice for the same offense, and forbids forcing anyone to confess or testify against themselves.

When taken together, these clauses support the principles of due process, rule of law, and fair trial — the pillars of criminal jurisprudence in India.

Clause-wise Analysis and Judicial Interpretation of Article 20

A. Article 20(1): No Ex Post Facto Law

This clause prohibits retrospective criminal laws, ensuring a person is punished only for acts that were offenses when committed. It upholds legal certainty—a cornerstone of the rule of law.

Judicial Interpretation: Keshavan Madhava Menon v. State of Bombay (1951) — The Supreme Court ruled that a person cannot be tried under a law enacted after the act. Criminal statutes are meant to apply prospectively.

Modern Relevance: Especially in cyber law and digital offences, individuals cannot be punished for acts committed before a law existed. This ensures laws are applied fairly: “Nullum crimen, nulla poena sine lege” — no crime, no punishment without law.

B. Article 20(2): Protection Against Double Jeopardy

“No one should be tried twice for the same offense.” Once lawfully tried—acquitted or convicted—a person cannot face the same prosecution again, preventing harassment and persecution.

Judicial Interpretation: S.A. Venkataraman v. Union of India (1954) — Departmental proceedings don’t count as prosecution; double jeopardy applies only to actual court trials.

Contemporary Context: Critical in cases like white-collar crimes or tax evasion, where multiple proceedings may arise from the same circumstances.

Comparative Note: The principle mirrors the U.S. Fifth Amendment and the Magna Carta’s centuries-old fairness guarantee.

C. Article 20(3): Right Against Self-Incrimination

“No accused shall be forced to testify against themselves.” Confessions must be voluntary; the burden of proof lies with the State. It preserves human dignity and prevents coercion or torture.

Scope: Applies to accused persons, not witnesses. Protects oral or documentary evidence obtained under duress but not physical evidence like fingerprints or DNA.

Landmark Case: Selvi v. State of Karnataka (2010) — Narco-analysis, polygraph, and brain mapping tests require consent; forced use violates Articles 20(3) and 21.

New Law Reference: Criminal Procedure (Identification) Act, 2022 allows collection of biometric/biological samples in certain cases. Its compatibility with Articles 20(3) and 21 is debated.

Current Relevance: In an era of digital surveillance, AI-assisted investigations, and forensic profiling, courts increasingly interpret this right to protect voluntary evidence and privacy

Current Relevance & Contemporary Debates

The brilliance of Article 20 is its timelessness. drafted in 1949 with principles that are endlessly evolving with respect to the changing nature of crime, technology, and governance. In this age of digital and security, it remains a living safeguard – requiring a constant reinterpretation of liberty without compromising.

a. Technology’s Emergence and our Privacy

The digital revolution expanded the scope of justice, but this came at a cost to privacy. Investigative agencies use AI-based forensic tools, facial recognition technology, and metadata to trace offenders. However, this brings serious questions:

Is the act of extracting information from a mobile phone, cloud storage service, or social media account, without informed consent, self-incrimination under Article 20(3)?

If the accused is compelled to unlock the phone, using biometric authentication, is that a form of testimonial compulsion?

The courts of India are still working and struggling through these grey strands. In Puttaswamy’s 2017 judgment (Right to Privacy), the Supreme Court has already established privacy as a fundamental right, which means no attack against privacy can stand unless it satisfies the tests of legality, necessity and proportionality. Therefore, Article 20(3) serves as a constitutional protection against technological coercion.

“Technology should be a facilitator of justice, not a corrosive of liberty.”

b. Preventative Detention and National Security

In the age of international terrorism, financial crimes and digital spying, laws such as the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA), National Security Act (NSA) and the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA) have become critical to national security.

However, these heavy laws are all conflated with security and liberty.

Global Comparisons

India’s Article 20 finds close cousins in other liberal democracies:

| Country / Document | Provision | Key Principle |

|---|---|---|

| U.S. Constitution – Fifth Amendment | “No person shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself.” | Protection against self-incrimination & double jeopardy. |

| European Convention on Human Rights – Article 7 | “No one shall be held guilty of any criminal offence on account of any act which did not constitute a criminal offence at the time when it was committed.” | Prohibits ex post facto punishment. |

India’s framers studied these precedents but crafted Article 20 with a distinct moral depth, balancing individual dignity with societal order.

Seven decades later, it continues to showcase India’s constitutional maturity and global alignment with human rights jurisprudence.

Famous Judicial Pronouncements Shaping Article 20

| Case | Year | Key Principle Established |

|---|---|---|

| Keshavan Madhava Menon v. State of Bombay | 1951 | No retrospective criminal law; Article 20(1) is prospective. |

| S.A. Venkataraman v. Union of India | 1954 | Clarified that departmental proceedings ≠ prosecution; defined double jeopardy limits. |

| M.P. Sharma v. Satish Chandra | 1954 | First major interpretation of self-incrimination; emphasized voluntariness. |

| State of Bombay v. Kathi Kalu Oghad | 1961 | Physical evidence (fingerprints, handwriting) ≠ testimonial compulsion. |

| Selvi & Ors. v. State of Karnataka | 2010 | Narco-analysis, polygraph, and brain-mapping without consent violate Article 20(3). |

| V. Senthil Balaji v. State | 2023 | Reaffirmed due process and fair treatment even in economic offences. |

Article 20 guarantees that while the State may act with force, it should never act with inhumanity.

Case Reference: V. Senthil Balaji v. State (2023)

The Supreme Court reiterated once more that the right to a fair process cannot be compromised even when a state authority investigates economic offences.

Due process and the presumption of innocence are not privileges; they are requirements of the Constitution, applicable even to the most potent enforcement agencies.

“Liberty is not a gift of the State; it is the foundation of constitutional democracy.”

Connecting the Ancients to the Moderns

From the Dharmashastra to the Greek polis to the Mughal Qanoon-e-Adl to the Age of Enlightenment, man’s search for justice has depended upon intent, equity and proportionality.

Article 20 is central to this fusion, a combination of moral philosophy and contemporary constitutionalism.

“Injustice is the constant and perpetual will to assign to every man his due.” — Ulpian, Roman jurist.

This vision echoes throughout aligned through and Indian constitutional morality:

- From Dharma to Due Process

- From Dandaneeti to Criminal Jurisprudence

- From Kautilya to Ambedkar

Every age further proved the same timeless truth; law must be for justice and not for authority.

Article 20 expresses India’s living commitment to this truth; to ensure that even when the State prosecutes, it is done with conscience, compassion and accountability.

UPSC & Governance Relevance

| Aspect | Details / UPSC Linkage |

|---|---|

| Prelims Focus | Frequently asked under Fundamental Rights (Article 12–35), especially Rights of the Accused and Criminal Justice provisions. |

| Mains – GS Paper 2 | Appears under themes like Judiciary and Constitution, Rule of Law, Due Process of Law, and Criminal Justice Reforms. |

| Ethics (GS Paper 4) | Reflects Judicial Ethics, Accountability, and Fairness in Decision-Making. |

| Governance Context | Strengthens trust in institutions by ensuring state power is exercised within legal and moral limits. |

| Contemporary Application | Relevant in debates on data privacy, AI in investigations, preventive detention laws, and individual liberty versus state security. |

| Keywords for UPSC Answers | “Due process,” “Rule of Law,” “Rights of the Accused,” “Constitutional morality,” “Checks on arbitrary power.” |

Conclusion: The Justice of the Constitutional Compass

Article 20 is not just a procedural safeguard; it is a moral check on the abuse of power. It ensures that justice in India is humane, not mechanical, consistent with universal human rights values and our civilizational values.

“Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” – Lord Acton.

Consequently, Article 20 serves as the moral compass of the Constitution, making certain that even our quest for justice prioritizes the dignity of the individual.

FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

1. What is Article 20 of the Indian Constitution?

Article 20 provides protection in respect of conviction for offences. It safeguards individuals against retrospective criminal laws, double punishment, and forced self-incrimination.

2. Why is Article 20 considered crucial in criminal law?

It ensures fairness in trials by preventing arbitrary punishment and coercive investigation practices—forming the foundation of India’s criminal jurisprudence.

3. Does Article 20 apply to civil cases or only criminal ones?

It applies only to criminal offences. Civil laws can operate retrospectively, but criminal laws cannot punish for acts committed before their enactment.

4. What are some famous Supreme Court cases interpreting Article 20?

Key cases include Keshavan Madhava Menon v. State of Bombay (1951), S.A. Venkataraman v. Union of India (1954), Selvi v. State of Karnataka (2010), and V. Senthil Balaji v. State (2023).

5. How does Article 20 relate to modern issues like data privacy and AI investigations?

With digital forensics and AI-based surveillance expanding, courts must balance technological investigation with the right against self-incrimination and privacy under Article 20(3).